Sugars That Glow Could Explain Ocean Carbon Mysteries

Scientists have created a glowing molecular probe that lets them watch marine microbes digest sugars in real time. This breakthrough tool reveals how algae and bacteria interact in the ocean and how carbon moves through marine ecosystems.

By lighting up when sugars are broken down, the probe exposes which microbes can consume specific complex carbohydrates and how this affects carbon storage on the seafloor. The discovery opens a new window into understanding the ocean’s carbon cycle and the microscopic processes that shape our planet’s climate.

Illuminating Ocean Chemistry

A group of chemists, microbiologists, and ecologists has created a molecular probe (a molecule designed to detect e.g. proteins or DNA inside an organism) that glows when a sugar is broken down. In their report in JACS, the researchers explain how this probe allows them to observe the tiny but crucial struggle between algae and the microbes that feed on their sugars in ocean environments.

“Sugars are ubiquitous in marine ecosystems, yet it’s still unclear whether or how microbes can degrade them all,” says Jan-Hendrik Hehemann from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology and the MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, both located in Bremen. “The new probe allows us to watch it happen live,” Peter Seeberger from the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces adds.

Sugars Capture Carbon in the Deep

Algae absorb carbon dioxide and turn it into oxygen and organic matter, with sugars serving as a major part of this process. However, not every sugar is easy to break down. Some are so complex that only a few microbes have the right tools to digest them. As a result, some of this carbon sinks to the ocean floor, where it can remain trapped for centuries until the proper enzymes appear.

Scientists have long tried to determine which microbes can digest which sugars, a puzzle made difficult by the enormous diversity of marine microbial communities.

Lighting Up Sugar Breakdown With FRET Technology

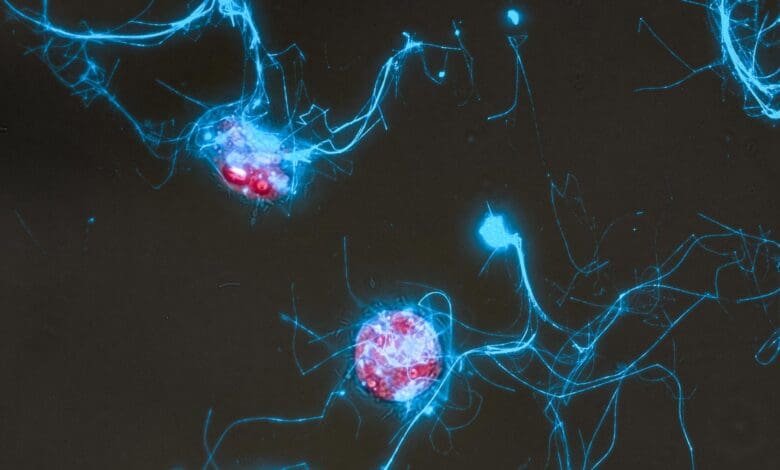

To tackle this challenge, the team used automated glycan assembly to produce a sugar tagged with two fluorescent dyes. These dyes interact through a process known as Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), working together like a molecular switch. When the sugar molecule is intact, the probe stays dark. Once an enzyme cuts through the sugar’s backbone, the probe begins to glow. This reaction lets scientists see exactly where and when sugar degradation is taking place.

The team tested the tool by following the breakdown of α-mannan, a polysaccharide (long sugar chain) commonly found in algal blooms. The probe functioned successfully across multiple test systems, including purified enzymes, bacterial extracts, living cultures, and full microbial communities.

“This research is a wonderful example of interdisciplinary collaboration between Max Planck Institutes. With our FRET glycans, we now have a new tool for researching phytoplankton-bacterioplankton interactions in the ocean,” says Rudolf Amann from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology.

Revealing Hidden Degraders and Carbon Cycle Secrets

By enabling the tracking of α-mannan turnover, this glycan probe opens up new avenues for studying microbial metabolism without the need for prior genomic knowledge. Researchers can now pinpoint active degraders in situ, map the progression of glycan breakdown through space and time, and quantify turnover rates in complex communities.

This tool paves the way for deeper insights into glycan cycling across ecosystems, from ocean algal blooms to the human gut. By observing which microbes are activated and under what conditions, scientists can link specific enzymatic activities to environmental processes and ultimately gain a better understanding of carbon flux in the ocean.

“Sugars are central to the marine carbon cycle,” concludes first author Conor Crawford from the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces. “With this FRET probe, we can ask: Who’s eating what, where, and when?”

Reference: “Activity-Based Tracking of Glycan Turnover in Microbiomes” by Conor J. Crawford, Greta Reintjes, Vipul Solanki, Manuel G. Ricardo, Jens Harder, Rudolf Amann, Jan-Hendrik Hehemann and Peter H. Seeberger, 8 July 2025, Journal of the American Chemical Society.

DOI: 10.1021/jacs.5c07546

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google, Discover, and News.